You are browsing the Music Resources category

Sleep Deprived Cooked Alive is a drum & bass track from my album Rhythm and Xen. It’s written in 14-EDO (a microtonal tuning). It’s definitely one of the more popular tracks, so I’ve decided to release the remix stems for free.

Download the Sleep Deprived Cooked Alive remix stems pack

The pack includes audio stems, MIDI parts and tuning files to help you tune your synthesizers to 14-EDO. Refer to your synth’s manual to see if it supports these files. This should be enough to get a good remix going, or just to study my work if you’re learning microtonal music.

If you make anything with these stems then let me know! I would love to check it out.

Sleep Deprived Cooked Alive (stems pack) by Sevish is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at https://sevish.bandcamp.com/track/sleep-deprived-cooked-alive.

I was reading some of Ivor Darreg’s writings and a really interesting idea jumped out.

“Try this: Move the bridge down until the 13th (instead of the 12th) fret sounds the octave of the open string. This will give an approximation of the 13-tone equal temperament.”

Here’s how it works. If you have a guitar with a movable bridge, then you can move it down such that the 13th fret gives you a perfect octave. This gives you a 13 tone scale to play on your guitar!

While its approximation to 13-edo is far from perfect (you’d need to completely move the frets for that) this should offer plenty of new tonal resources to the experimenting microtonal guitarist. Compared to 13-edo, the error is largest in the middle of the scale.

You can reverse this and push the bridge up such that the octave lies on the 11th fret, giving you a brand new 11-tone scale to experiment with. Again, it poorly approximates 11-edo but don’t worry about that, there are plenty of new sounds available through this method.

The idea can be pushed further:

“I fretted a guitar to 18-tone (Busoni’s proposed third-tones) and can use this guitar as a 17 or a 19 without the theoretical errors from moving the bridge spoiling any performances. So you can have three systems for the price of one.”

This really is “one weird trick that luthiers don’t want you to know!” Bwaha… ok I’ll see myself out the door.

For something a little different, check out 9 Alternative Tunings NOT for Guitar.

[Update Jan 2023: This article is quite old now. If you’re looking for something more user-friendly than Scala, try Scale Workshop. If you want to learn more about Scala, read on!]

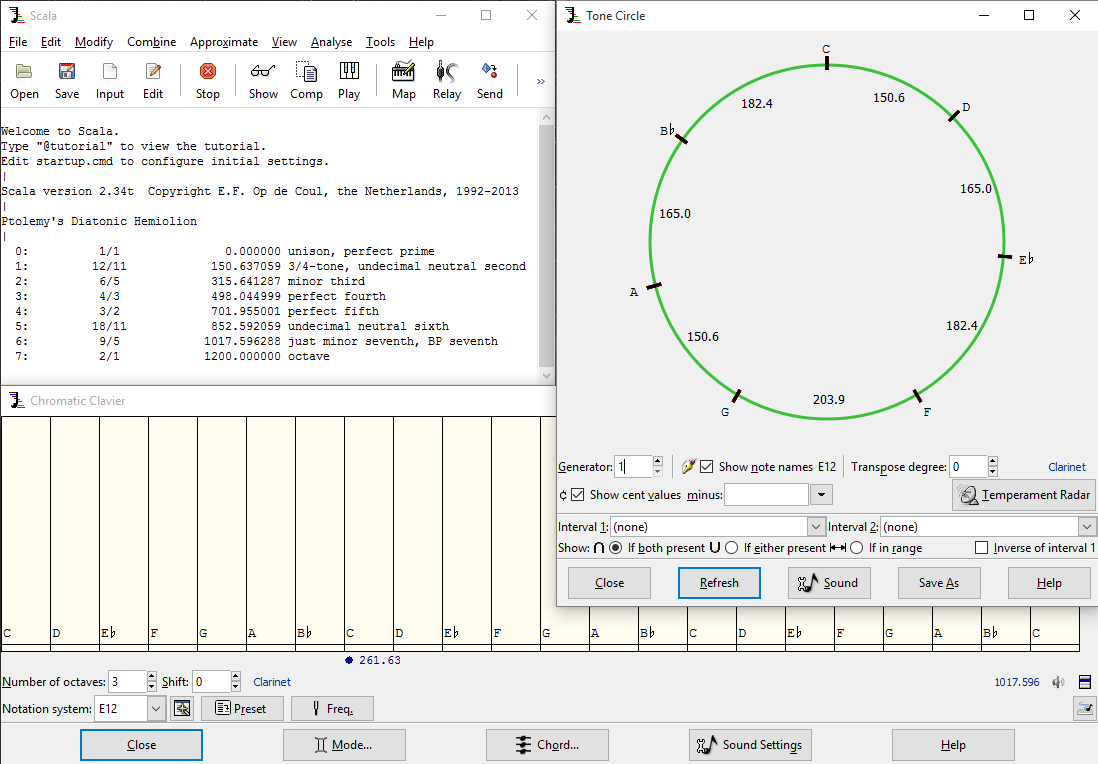

When you want to edit photos, there’s Photoshop. When you want to listen to music there’s iTunes (if you’re a pro at life, there’s foobar2000). When you want to create your own musical scales, opening up endless possibility in harmonic and melodic expression, there is Scala. Scala is a multi-purpose toolkit for everything related to tunings, scales and microtonality. You have a hardware synth that you want to retune? Scala will do it. Or a softsynth? Scala can export the tuning files required to make that happen. Want to generate all kinds of crazy scales that you can use to compose new music? Scala has near infinite options for you to play with. Want to experiment with world music and historical scales? There’s a database of thousands on the Scala website.

Equal temperaments are scales that divide an octave into some number of equally big pieces. The 12 note scale of Western music is an example, as each semitone is of equal size. So you already have experience with equal temperament scales and didn’t know it.In Scala, equal temperaments are trivially easy to create!A popular thing that beginning microtonalists like to do is to try quarter tones. The quarter tone scale divides the octave into 24 notes. Let’s make the scale in Scala. Load up Scala, type this line into the text field at the bottom, then hit enter:

equal 24

Explanation: When you type the command equal, followed by a number, Scala will produce an equal-tempered scale with that number of notes in an octave.But it looks like nothing happened after we hit enter. We still need to check that the scale was created correctly. So type:

show

This will show you the tuning data for the equal temperament scale you just created. As below:

0: 1/1 0.000000 unison, perfect prime 1: 50.000 cents 50.000000 2: 100.000 cents 100.000000 3: 150.000 cents 150.000000 4: 200.000 cents 200.000000 5: 250.000 cents 250.000000 6: 300.000 cents 300.000000 7: 350.000 cents 350.000000 8: 400.000 cents 400.000000 9: 450.000 cents 450.000000 10: 500.000 cents 500.000000 11: 550.000 cents 550.000000 12: 600.000 cents 600.000000 13: 650.000 cents 650.000000 14: 700.000 cents 700.000000 15: 750.000 cents 750.000000 16: 800.000 cents 800.000000 17: 850.000 cents 850.000000 18: 900.000 cents 900.000000 19: 950.000 cents 950.000000 20: 1000.000 cents 1000.000000 21: 1050.000 cents 1050.000000 22: 1100.000 cents 1100.000000 23: 1150.000 cents 1150.000000 24: 2/1 1200.000000 octave

Explanation: The equal command that we just used has produced 24 items for us (24 notes in our scale). The show command lets us see those 24. Each of these shows some number of “cents.” The cent is a measurement of how wide or narrow an interval is. Notice that each interval in our 24-equal scale goes up by 50 cents. 50 cents is exactly one quarter tone. 100 cents makes up a semitone, and 1200 the whole octave. Cents are a useful measurement to get your head around if you want to compare tunings with each other.That’s enough staring at numbers. Time to hear these quarter tones for the first time. On the Scala interface you’ll see a button which says play. Click that button!

In the first part, we divided an octave into some number of equal parts. Amazingly, we are not limited to dividing octaves. We can choose to divide other intervals instead, such as a perfect fifth or whatever you like. But what’s the point?Every note in a non-octave scale has a unique identity. Consider that we know a note A as a note oscillating at 440 Hz, or some octave above (880 Hz, 1760 Hz) or below (220 Hz, 110 Hz, 55 Hz). If our scale doesn’t include octaves, then a note A won’t have any other counterparts higher or lower in the scale. This means that, as we climb up or down into different registers, we keep hitting unique note identities which haven’t been heard elsewhere in the scale!This approach is extremely fruitful for new sounds, sonorities and progressions. However composition technique must change drastically. For starters, there are no more chord inversions, since you can’t raise any notes up or down an octave. Of course, this makes voicing difficult too. But you gain a very wide variety of intervals to play with, and it will challenge and grow you as a composer to exploit non-octave scales. Just try it and see.Here’s how we do it. We’re going to create a scale which divides a perfect twelfth (an octave plus a fifth) into 13 equally spaced parts.

equal 13 3/1

Explanation: The equal command tells Scala that we’ll be making a scale where all notes are the same size. The number 13 shows that we want 13 notes. And that weird fraction on the end? That’s the big interval that will be split into 13 equal parts. Think of it as a pseudo-octave.Why 3/1? For now just take my word for it. 3/1 is a perfect twelfth. So rather than repeating at the 8th (octave), we’re repeating at the twelfth.Notice, if we don’t include the number 3/1, then Scala will assume that this is an octave based scale. (An octave, by the way, can be expressed as 2/1).Let’s see the cents values for the scale we created:

show

And the result:

0: 1/1 0.000000 unison, perfect prime 1: 146.304 cents 146.304231 2: 292.608 cents 292.608462 3: 438.913 cents 438.912693 4: 585.217 cents 585.216923 5: 731.521 cents 731.521154 6: 877.825 cents 877.825385 7: 1024.130 cents 1024.129616 8: 1170.434 cents 1170.433847 9: 1316.738 cents 1316.738078 10: 1463.042 cents 1463.042308 11: 1609.347 cents 1609.346539 12: 1755.651 cents 1755.650770 13: 3/1 1901.955001 perfect 12th

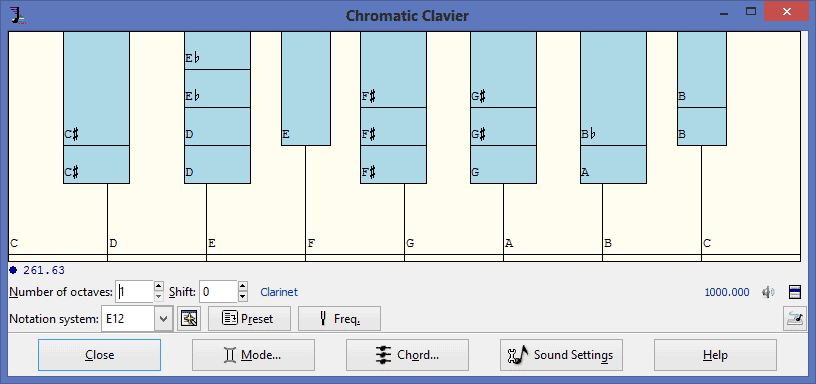

Can you remember how many cents are in an octave?The answer is 1200 cents. Looking at the above list of intervals, we can see there’s no value too close to 1200 cents at all. But there’s this nasty 1170 cents interval that’s gonna sound noticeably flatter than an octave. On the other hand, that perfect twelfth at 1901.955 cents, is purely in tune. Whatever this scale is, it doesn’t represent anything we’re used to in Western music. There’s no perfect fifth, no octave…The scale we’ve just created is none other than the Bohlen-Pierce scale, a famous non-octave scale with many interesting properties. It sounds very alien until you have taken time to immerse yourself in it. Jam with the chromatic clavier and hear it for yourself (remember, just click the play button on the Scala interface to do this).

The topic of just intonation (JI) is deserving of several books in its own right. It is an old mathemusical theory in which many cultures have their own take.What could a name like “just intonation” mean… If you think of “just” as meaning fair, right, exact, and perfect – and intonation of course having to do with the accuracy and flavour of the pitch – then you should get the general idea. Just intonation is a tuning system that uses exact, perfect intervals.In fact, the pitches of just intonation are made up of ratios. Think of numbers such as 2/1, 3/2, or 15/8. (These intervals are an octave, perfect fifth and major seventh, respectively).

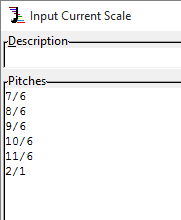

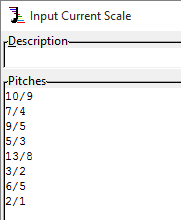

Time to get creative! There are many ways to go about making your own just scale, but here’s one way that can get you exploring quickly.On the main Scala window, click on the Input button to open up the Input Current Scale window. Here you can enter the pitches you want to use. In this case we’ll enter some fractions at random, following some simple guidelines.

Below are a few examples that follow the above guidelines.

You can also use Kyle Gann’s anatomy of an octave to find some interesting numbers to plug in.Once you’re done, hit OK and you’ll be taken back to the main Scala window. At this point you will find 9 times out of 10 that Scala says “Scale is not monotonic ascending.” If you saw this message then it means that the pitches of your scale are in a weird order. To fix this issue, tap the Edit button on the main Scala window, tap the Ascending button, and finally click OK.Let’s take a quick look at what you made:

show

Take a quick look at the interesting names that Scala gives to the ratios you randomly chose.Now it’s time to hear your scale! Hit the Play button to show the Chromatic Clavier. You can hold shift when you click to hold multiple notes down and hear that solid JI sound.Alternatively you can play your scale using a connected MIDI controller or MIDI keyboard. To do this just click the Relay button on Scala’s main window and then click the Start Relaying button.Repeat this process of JI scale creation a few times, each time playing your scale using a keyboard to get a feel for the unique musicality of each one.Once you become comfortable with this process and you get to know certain ratios that you love the sound of then you can start to ignore the guidelines I gave before.

Now you know how to come up with a just intonation scale of your own. But you still might not know why you would want to use just intonation. There are many differing opinions out there and it’s easy to find them using Google. And I recommend you spend a lazy afternoon doing just that. Here are a few suggestions:

It goes without saying (actually maybe it doesn’t) that if you want to make microtonal music, you need to have the right tools. For my album Rhythm and Xen I found the perfect set of tools that worked for me to get the sound that I wanted. And all while bending notes like a madman.

Stream and download Rhythm and Xen

First the machine: I produced half the tracks on a home-built desktop computer running Windows 7. The other half were produced on an Acer laptop running Windows 8. That should tell you there’s no need to get fancy and expensive, just grab a computer made within the last 5 years and start writing.

My DAW of choice is Ableton Live 9. I used to be an FL Studio user – a really common phrase for my generation – but when I picked up Ableton Live I preferred the workflow and the base functionality. There was no looking back.

As for the default synths that come with Live, throw ‘em out. They can’t be microtuned, so they’re only good for making music that everybody else makes.

For me, the key to making microtonal music in a DAW is to find some microtunable VSTs that you like the sound of. So here are the 5 VSTs I used in Rhythm and Xen:

I love the sound design potential of this synth, and the VA waveforms sound nice for a digital synth.

FM synthesis built from the ground up to get spectrally microtuned sideband partials… what’s not to like? And if you have no idea what I’m talking about, it’s just a good FM synth. :)

Virtual analog with some weird characteristics, quirky yet bold.

It’s a SoundFont player. When you’re craving some 12-bit sounds.

An affordable orchestral sound bank, nuff said. Sadly, the more I work with GPO4, the more I can recognise it from a mile off. So now that Rhythm and Xen is complete I’m gonna retire this one.

As far as VST instruments go, these 5 were all I needed. Although, I did create a couple of my own sound generators in Max/MSP to fulfil other needs. But if you’ve seen my downloadable music resources then you already know what those are.

FX wise, I just love the collection from Variety of Sound. NastyDLA is all over this record, and I used some of their bus compressors in mastering. These plugins are amazing and free!

Oli Larkin’s Endless Series v3 is a really unique effect which can generate Shepard tones, endlessly rising tones. But the killer bit is, it can do endlessly rising or descending phaser and flanger effects too. You can create a sense of urgency doing this (great risers), or else just come up with some cool sound designs.

Download the album: https://sevish.bandcamp.com/album/rhythm-and-xen

Dr. Ozan Yarman has recorded his qanun and compiled this beautiful SoundFont for you to use in your own work.

http://ozanyarman.com/wpress/2015/01/kanunqanun-soundfont/

Qanun SoundFont (tuned exactly to 12 equal pitches), based on sampled sounds that I obtained from my 79-tone qanun during the Summer months of 2008, which I prepared using PolyPhontics + Audacity at the beginning of 2015.

Try playing Dr. Yarman’s qanun in a SoundFont player that is capable of rendering Turkish or Arabic maqam/makam scales faithfully, such as OneSF2 (Windows, free), Scordatura (Mac OS X, free), or microsynth (Mac OS X, $20) and you’re good to go!

I have made another tuning pack available—world scales! The pack contains tuning files used to retune various synthesisers. The following formats are supported: Scala (.scl/.kbm), Anamark TUN (.tun), MIDI Tuning dump (.mid).

The world is a massive place, with many creatures living on its surface. One such creature is called the human. Humans all over the world just love to make music; it’s one of a few things that can unite us all. But where you go in the world, you’ll notice that the musical scales differ just as much as the food, the clothes, the language, the customs, the creation stories…

Download the world scales tuning pack.

It contains Ancient Greek, Arabic, Bulgarian, Chopi, North Indian (Hindustani), Indonesian, Japanese, Macedonian, Scottish, Thai, and Zimbabwean scales. A concise and tidy starter pack to sample what’s out there.

If you’re looking for scales to take your music to a transcendental place, then these long-lived musical traditions may have something for you. And if you’re looking for something a little different, I have other tuning packs on my music resources page.

Those of you who have built synths in Max/MSP or Max 4 Live will have used the mtof (MIDI-to-frequency) object. This clever little object waits for you to send it a MIDI note number (0-127), then it spits out a frequency (Hz). Perfect if you’re working within the confines of 12-tone equal temperament—or rather limiting if you wish to use all kinds of expressive intonation systems outside of the Western common practice.

There is a very simple way to get microtonal scales out of your Max/MSP synths. We simply replace the mtof object with coll.

Coll can be used to store and edit collections of data. The data is stored in a text file. Each item of data contains an index followed by some content. For example, we could use coll to remember the release years for various killer synths.

Above, the coll object is waiting to receive an index (either YamahaDX7 or Theremin) before it spits out the data we want. I just clicked the “YamahaDX7” button, so “1983” was sent via the first outlet of coll.

To see and edit all the data inside the coll, just double-click on the coll object. It will bring up the data entry window. Here’s what’s inside the above coll object:

OndesMartenot, 1928; RolandTB-303, 1982; Theremin, 1920; YamahaDX7, 1983;

Neat trick. Mind you it’s not very useful for our goal of exploring crazy scales.

Here’s how we can use coll as a replacement for mtof. First we need to understand our data structure. We send a MIDI note number (0-127) to the coll object. We want coll to spit out a frequency in Hz. So we double click coll, and we start inputting data for what frequency corresponds to what MIDI note number.

# Lines that start with a # symbol are comments. # This is a simple scale which starts at 100 Hz on MIDI note 0. 0, 100.0; 1, 200.0; 2, 300.0; 3, 400.0; 4, 500.0; 5, 600.0; 6, 700.0; ... 127, 12800.0;

(Interesting note: This scale is a harmonic series with a fundamental of 100Hz. Kinda trippy if you’ve never heard this kind of scale before, so try it out).

To test this out, let’s send the number 0 to the coll. This is the lowest possible MIDI note number, and according to our data we should receive the float value 100.0 from coll’s first outlet.

A success! It’s pretty simple to get it to work, but the only problem is that the tuning data took us a looooong time to type… 128 lines in total! Luckily coll can read .txt files, and there is a much better way to generate tuning data in this format. For this tutorial, we’ll be using Scala tuning software to create .txt files that coll can read.

First create or load some tuning data into Scala. (For now we’ll just load a file from Scala’s huge database)

Then type the following command into Scala:

set synth 135

Scala will say “Synthesizer 135: Max/MSP coll data, via text file”. You’re doing just great.

Now click File → Export synth tuning as shown below.

This will bring up a familiar save file dialog, and you can save your .txt file anywhere. Once your .txt file is saved somewhere convenient, your can load it into your coll object.

Create a message button which contains the word “read”. Connect this up to the coll object (as shown below). You can click the “read” button to bring up an open file dialog. Use this to load the file you just exported from Scala.

Once you’ve loaded the .txt file into coll, you can check that the data went in correctly by double-clicking the coll object.

# Tuning file for Max/MSP coll objects created by Scala # # Sean "Sevish" Archibald's "Trapped in a Cycle" JI scale 0, 8.1757989; 1, 8.4312926; 2, 9.1977738; 3, 9.5384321; 4, 10.2197486; 5, 10.7307361; 6, 11.2417235; 7, 12.2636984; ...

Congrats, you’ve just replaced the mtof object with your very own, microtunable coll! Enjoy playing microtonal scales in Max/MSP.

Big up to Manuel Op de Coul, the creator of Scala, who added support for Max/MSP coll files on my request. Much appreciation that his project is still being maintained.

This article has been updated in 2023 to tell you more ways to make microtonal music with software synthesisers.

Many software plugins (VST, AU, RTAS etc.) allow you flexible control over intonation, which can be used to create music with any tuning system you like. There is no one single method, so depending on your synth, you’ll be able to get at those microtones with one or more of the following:

Plugins that don’t support any of the above may still be tuned by systematically using the pitch bend, however this only works for monophonic parts (unless you use multiple instances of the same plugin).

To find out how your synth can be microtuned, look it up in this table of microtunable software plugins. From there you’ll also find a few free VST downloads to experiment with.

If your softsynth loads .tun files (AnaMark, Linplug instruments, Omnisphere, etc.) then check out my tutorial on how to create a .tun file using Scala.

If you’re using something like Surge XT, PianoTeq, ZynAddSubFX, Plogue chipsounds or Garritan Personal Orchestra 4 (amongst others), these synths can load .scl files. It’s simple to find this kind of file for download on the internet, and they are easily created using Scale Workshop.

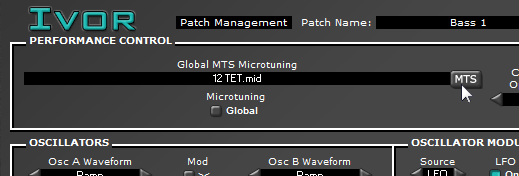

Synths that support MTS-ESP will need an MTS-ESP master plugin to control the tuning. Some examples of MTS-ESP master plugins:

The MTS never really took off in the same way that MTS-ESP and MPE is taking off in recent years. In my experience, a lot of the MTS-capable synths are hardware and not software.

Synths such as Xen-Arts’ instruments can be tuned by using MIDI tuning messages. Such data can be generated by software like Scala, alt-tuner, CSE or LMSO. Then, the data is either sent to the synth in real-time or dumped into a file to be read later.

One approach is to include the MIDI tuning messages in a MIDI track within your DAW. The MIDI track should output to all tracks which contain an instance of the synth. This approach works well in a DAW like Reaper, which has powerful routing. Unfortunately this approach won’t work in Ableton Live or FL Studio, because these DAWs filter out all SysEX data, thereby stopping your synth from receiving the MIDI tuning messages.

[Note: Xen-Arts synths are no longer available]

Direct note input is not a common feature of synths, but there are a few:

Just a quick microtuning tutorial. Are you using a synthesizer instrument which loads the TUN (.tun) tuning file format? Let’s learn how to create one of these .tun files using Scala.

Before you start, make sure you’re using a synthesiser that supports .tun files.

You could load a file from Scala’s huge scale database, or you could generate new pitches by typing a command into the command bar (at the bottom of the window). For example let’s create a 13 note equal scale (13-EDO):

equal 13

Tip: Type “show” to display your the tuning in the main window.

show

Type the following into the command bar:

set synth 112

Scala will output “Synthesizer 112: TUN standard .tun format for many softsynths, via text file”. You’re doing OK.

Go to File > Export synth tuning. Or press Shift+Ctrl+T instead. Choose a new location to save the file. All done!

This is very similar to the process of making a MIDI Tuning Standard (MTS) tuning dump. To make an MTS .mid file, use “set synth 107” instead.

Jam away!