You are browsing the Linux category

Version 1.8.0 of Decent Sampler offers microtuning support via the Tuning menu. You need to supply it with an scl and kbm file, which can be easily generated with Scale Workshop, Scala, or other tuning creation tool.

Surge XT is a software synth plugin. Version 1.2 is now released. This version improves upon its tuning functionality, accessibility and other things. An excerpt from the changelog reads:

Major Feature: Tuning Upgrades

- Surge can act as an OddSound MTS provider (‘master’) allowing the Surge tuning editor to provide tuning to an entire session.

- Remediate yet more edge cases in our internal tuning, including keyboard mapping larger than a scale.

The short explanation is, if you are using synths that support tuning via MTS-ESP, Surge XT can now act as the MTS-ESP master, which means that you specify your tuning within Surge XT and then the other synths will follow the same tuning. This is intended to be more convenient than loading the same tuning data into multiple instances of various synths.

Surge XT is free and available on Linux, Windows and macOS.

This article explains some software and hardware I used to write a few of my albums. The workstation runs Linux, Bitwig Studio and various audio plugins. I also cover many alternative software choices here as your preferences might differ to mine. Updated 2023.

[The old article about my previous workflow for making microtonal music with Ableton Live is still available though quite out of date as Ableton have improved their microtonal support in recent years.]

You could probably get away with using a few year old laptop for sure. I have some kind of Intel Core i7 and 16GB DDR4 RAM.

If you want to record in from microphones or hardware synths then you’ll also want to get an audio interface. I just got a cheap one that said it was USB class compliant. 2 ins, 2 outs.

USB MIDI keyboards seemed to universally work for me on Linux. Isomorphic keyboards such as my C-Thru AXiS-49 work well for microtonal music because scale and chord fingerings remain the same in each key, whereas a standard MIDI keyboard requires you to learn a different fingering for each key. The keys are all nerdy lil hexagons, it’s cute. It just plugs in via USB and my system recognises it instantly as a MIDI input device.

I bought a second hand M-Audio Keystation 88es for 50 quid. Good deals can be had if you buy used. It’s my preferred MIDI controller; I even prefer it over the AXiS-49! There’s something about the traditional 1-D style keyboard that feels natural to play.

Which Linux distribution is a personal preference and I can’t hope to do the question justice. To replicate my setup you want any Debian-based distro so you can use the KXStudio repository (more about the KXStudio suite of tools later).

The distro I’m using is KDE Neon which is based on Ubuntu. I find KDE Plasma to be familiar, fast, with possibly too many options for customisation. Of course audio software demands that your desktop environment be as lightweight as possible. XFCE and MATE are two other lightweight and popular desktop environments worth trying.

If you just want sane defaults for audio work then Ubuntu Studio gives you get the low latency kernel and other audio tweaks set up by default. Think they have PipeWire now and of course KDE so I’m thinking to switch to Ubuntu Studio next time I nuke and pave.

For Arch-based distros, the AUR has an impressive selection of audio software.

I’ve been using KXStudio applications to deal with audio on my Linux music workstation. There are quite a few tools in KXStudio so here are the ones I find especially useful:

Cadence is a set of tools for audio production all in one application. It performs system checks, manages JACK, calls other tools and make system tweaks. It launches automatically when I boot, so I can then launch my DAW and get straight to doing music.

Carla is a plugin host that can load up various Linux synths and effects. There’s even a way to load Windows VSTs with it but I haven’t taken the time to figure that out – I’m happy with Linux-native software currently. The reason Carla is so crucial for me is that it can be loaded not just as a standalone app but also as a Linux VST. This is extremely useful if your DAW only supports VST plugins but you want to use LV2 plugins too – Carla acts as a VST-LV2 bridge in this case.

You can install the KXStudio apps by first setting up the KXStudio repo in your package manager. The repo also contains a large number of music plugins so you can install them via your package manager rather than compiling manually. This is so useful! It even contains all the u-he Linux synths (you still need to pay for a license as they are proprietary) and Zyn-Fusion (the new interface for ZynAddSubFX)!

When doing any kind of real-time audio processing or recording, you’ll want to use the low latency kernel rather than the generic kernel. This may help prevent crackling and reduce your system’s audio I/O latency. If you’re using a distro that is designed for audio work such as Ubuntu Studio then you already have this kernel. Otherwise if you’re using a generic distro you should search online for how to install and use the low latency Linux kernel.

You should also add your user to the audio group. This gives your Linux user permission to use desktop audio devices.

These days I’m using Bitwig Studio as my DAW. I will explain why below and also mention a few alternatives.

As a former Ableton user I found it easy to switch over to Bitwig Studio. Bitwig has a native Linux version which works well with the apps I installed from KXStudio. It is not free software – you buy a license and then get 1 year of upgrades. You can continue to use your copy after the license expires but you don’t get feature updates until you redo the license.

Bitwig Studio supports Linux VST plugins, but note that it does not support Linux LV2 plugins. This is disappointing because many libre audio plugins use the LV2 standard and not VST. And this is why the Carla plugin host is so essential – it allows me to bridge LV2 plugins into Bitwig Studio!

Bitwig’s built-in synths support MPE polyphonic pitch-bend. Its piano roll allows you to detune each note individually using an intuitive interface. That does entail a lot of manual work but gives you unprecedented pitch control in a polyphonic setting. MPE is also quite future proof being that it’s part of the MIDI 2.0 spec. I’m waiting to see if future synths will work seamlessly with Bitwig’s implementation of polyphonic pitch-bend.

Some people will prefer using Bitwig’s polyphonic pitch-bend over my usual approach (which is to use plugins that can import tuning files – more on that further below)!

There are various alternatives to Bitwig Studio and I’ll mention a few below.

Ardour is one of the most widely used free-and-open-source DAWs for Linux. Supports MIDI and synth plugins, so you can use plugins to get microtones.

Reaper – I am told by many many people that it is simply the best DAW around. Its native Linux build is stable enough for serious use. The license is cheaper than most proprietary DAWs and the demo version gives full access to all features, including saving and loading projects, so you can try it fully before committing to support the devs.

Reaper also lets you customise the key colours and layout of the piano roll. This is one of those issues that only microtonalists seem to understand is useful!

Renoise is a tracker style DAW that runs natively on Linux and can be microtuned using the SCL to XRNI tool. It also supports plugins so you can get at those microtones that way.

LMMS comes bundled with a variety of synths, all of which support microtuning by default.

Many synths don’t support microtonal tunings (they are locked in to 12-tone equal temperament) so we’re only looking at synths that support custom tunings. Often times the synths that come bundled with your DAW don’t support it but there are exceptions, try it and see.

If you use synth plugins that have built-in microtonal support then it doesn’t matter which DAW you use, as long as your DAW supports plugins. Below is a showcase of Linux-native plugins with support for microtonal tunings.

Surge XT is a powerful open-source synth with an excellent implementation of microtonal tuning via .scl and .kbm files. It’s cross-platform and can run as an LV2 or VST plugin. You can also use it with VCV rack.

Vital is a wavetable synth which supports microtonal tuning via .tun or .scl/.kbm files. There is a free version and a paid version and I believe the source code has also now been released.

TAL-Sampler is my sampler plugin of choice because it’s fun to play, not overly complicated and supports microtuning by tun file, MTS-ESP or MPE. That’s three ways to choose to get at those tunings!

The great people at TAL now support Linux for all their plugins which is extremely welcome because I was using them before I switched over. The sampler is especially important because there aren’t many of those supporting Linux. But I also get a lot of use from TAL-Chorus-LX, TAL-DUB-X and TAL-DAC.

Modartt’s Pianoteq is well known in the music world for its rather good piano sound. It’s a physically-modelled piano – this has some benefits over sample-based pianos. First, it has a tiny footprint of just a few megabytes storage, as opposed to the gigs and gigs often required by sample-based pianos. Second, you can tweak the parameters of the physical model to get interesting variants on the typical piano sound. Here’s an example that will interest microtonalists: you could design a piano with quietened even harmonics (e.g. harmonics 2, 4, 6, etc.) so that the timbre will blend better with the Bohlen-Pierce scale (this scale features primarily odd harmonics). This kind of sound design possibility is pure excitement for nerds like me.

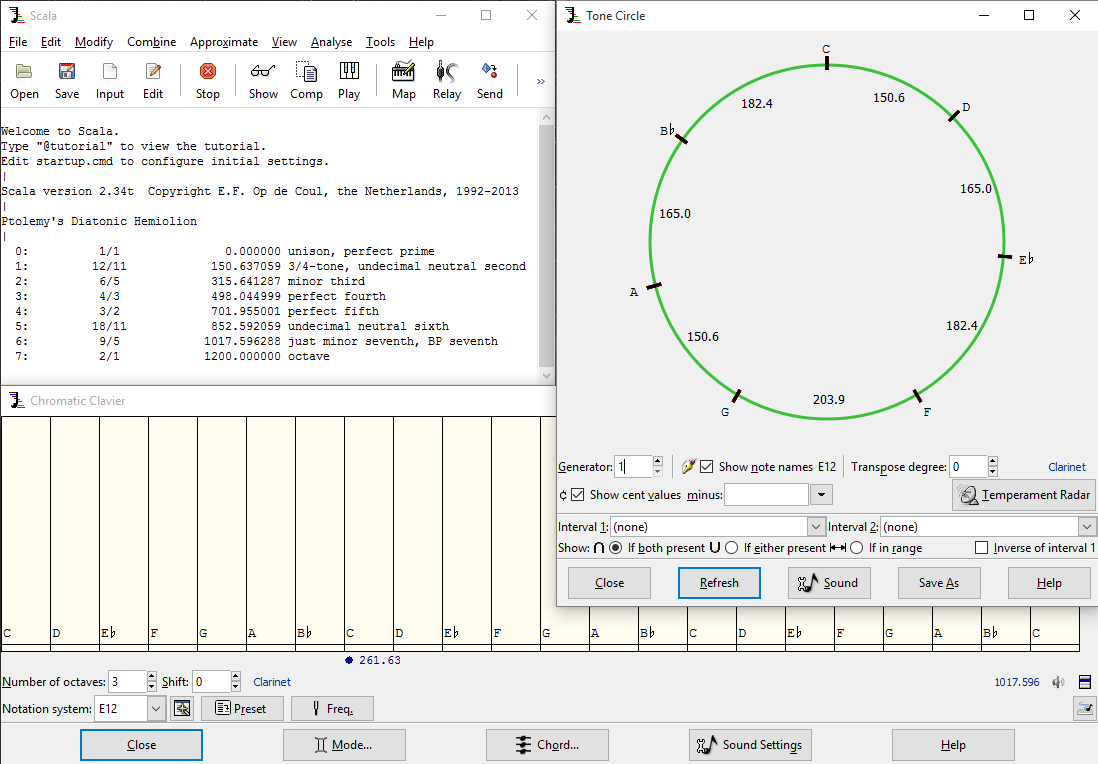

Pianoteq is a good example of how developers should implement Scala files support. It supports .scl files but also the .kbm format that allows the user to create any specific full-keyboard microtuning. Additionally they provide a tone circle graphic that allows you to visualise how the overtones of the piano timbre align with your tuning. That’s not necessary to have, but is a really nice feature.

Tip: on the tuning screen you usually must enable the ‘Full Rebuild’ option otherwise a great many tunings will sound unnatural and un-piano-like.

MTS-ESP is also supported as a method of microtuning, but last time I checked it had some sound quality issues. I’m recommending Scala files instead if you want to tune it.

Pianoteq supports Linux, macOS and Windows natively so it’s a good plugin for almost anybody who wants to write microtonal piano music. Just note that the Stage version has no microtonal support; you’ll need to get the Standard or Pro version if you want to retune the piano.

ACE – virtual semi-modular synthesizer

Bazille – virtual modular synthesizer

Diva – virtual analog synthesizer

Hive2 – wavetable synthesizer

Repro – virtual analog synthesizer

Zebra2 – various synthesizer

Many of the u-he synths have Linux versions available and can be microtuned using .tun file import.

Please be aware the Linux versions of our plug-ins are still considered beta. While the plug-ins are stable, we are not able to provide the same level of support for these products as we do for the macOS and Windows versions. Support is provided via the Linux and u-he communities on our forum.

I have a license for ACE and was using it on Windows for a few years. It’s nice to know that I can continue using it on my new setup.

EP MK1 is a free, physically-modeled electric piano plugin by Mike Moreno Audio. It has two methods for microtuning – you can dial in any equal temperament you want via the interface or you can load a text file containing a list of frequencies. The text file can be easily generated by Scale Workshop (I’m not sure if any other tuning software supports Pure Data text files).

I think EP MK1’s electric piano simulation is actually pretty usable within a mix. And with the recent addition of support for Pure Data text files it’s possible to tune every MIDI note to an arbitrary frequency. I finally have good reason to use this plugin on my next album.

Zyn-Fusion is a powerful synth capable of additive, subtractive, FM and PM synthesis. Really though you want this because its thick PADsynth sound can’t be imitated elsewhere. Zyn-Fusion can be microtuned by importing Scala (.scl) files and keymap (.kbm) files. Alternatively you can enter tuning data directly via the UI which might be helpful to some. While the developer of the new UI put so much effort into it, I feel like Zyn-Fusion still bugs out a lot and has rough edges. So I don’t really recommend this synth plugin anymore but it’s worthy of mention.

The v1 plugins (except for drumkv1) all support microtuning via .scl file.

synthv1 – a subtractive synth

samplv1 – a polyphonic sampler

padthv1 – an additive synth based on Paul Nasca’s PADsynth algorithm

As far as I’m aware samplv1 is the only microtonal-capable sampler plugin for Linux, so you will want to grab this!

kbm files are supported which means these synths can do full-keyboard microtuning. Your tuning can be saved per-instance or optionally saved as a system setting (in case you want to always use the same microtonal tuning in every instance).

This same developer also created the Qtractor DAW for Linux.

Amsynth is a subtractive synth and it’s quite easy to use.

Pure Data is a visual programming environment for audio similar to Max/MSP. It is free and very powerful.

Camomile is a VST wrapper for Pure Data patches. In other words, it allows you to turn your Pd creations into VSTs that you can load in to your DAW! It is cross-platform, so your creations can run on Linux, macOS and Windows.

The combination of Pure Data and Camomile is comparable to Max 4 Live.

Vinyl by Calf Audio is a vinyl emulation audio effect. So what, you ask. Well, it has one useful feature called ‘drone’ which applies an oscillating pitch-drifting to whatever audio you feed into it. If you dial in a lot of ‘drone’ you can recreate that warbly lo-fi tape-wow sound, or if you use just a little you can add a subtle intonation drift that will add interest to an otherwise perfectly accurate digital synth sound. Those of you who have composed just intonation music using digital synths will know the buzzing periodicity/phase-locking kinda sound. Just a little ‘drone’ adds enough error to the intonation to prevent that buzzing from happening.

Most synths don’t provide any interface for customising your own microtonal scales – instead they load a tuning file that you have to create yourself. For that, you’ll need some special software.

If you’re just getting started, try Scale Workshop – it can generate microtonal scales and export to a variety of tuning file formats. It’s free and open-source (MIT license). Because it runs in your web browser it doesn’t require installation.

For serious experimenters, you might want to graduate from Scale Workshop and use Scala. It’s also free, and can be installed by following the instructions on their official website. It’s not as user friendly as the alternatives but it has about ten thousand cool features hidden away.

If you want to re-tune hardware synths or use MIDI Tuning Standard then you will want to get Scala and not Scale Workshop!

This is the important bit!! Once you have created a tuning file using Scala or Scale Workshop, simply load it up in your synth of choice. Read your synth’s user manual for how to do this. Now you can jam away in your chosen microtuning.

As of 2023 I have released 5 albums that were produced on this Linux-based setup. So I’m serious when I say I prefer this OS and it hasn’t held me back as an electronic musician. If you’re curious about my sounds then head to sevish.com and hit play.

Are you making music on Linux, or making any kind of microtonal music? Let me know in the comments what works for you and how you got it running! Everybody has a different workflow and we can all learn something from one another.

My first experience with Linux was Fedora Core 3 in the early 2000s. It was neat but I wanted to play Stepmania and Rollercoaster Tycoon so I stuck with Windows. Later I got into music production. Again, Windows stuck. The spell was broken by Windows 10 which is literally so bad. I got back into Linux and saw how much it had matured. That’s when I committed to it.

(I do use macOS at work which is pretty good but this too is riddled with bugs and awkward design decisions).

The swap over to Linux was a gradual process as I had to learn a few things but I think I ended up with a solid system. Whenever I boot up the old Windows machine to revisit old projects I am quickly reminded how often I used to tolerate crashes on Ableton+Windows.

One issue remains with Linux that many audio software developers still target only Windows and macOS. I see this trend slowly reversing – and I have so much appreciation for developers who add support for native Linux. Have supported a few of these devs myself by purchasing their tools and sending in detailed bug reports when needed. Big respect to you all.

What you’re referring to as Linux, is in fact, GNU/Linux, or as I’ve recently taken to calling it, GNU plus Linux plus KDE plus JACK plus Bitwig Studio plus Carla plus Scale Workshop plus Surge XT.

A new web app called Scale Workshop allows you to design and play your own microtonal scales. You can also tune various other synthesizers with it. It has just reached version 1.0 and is now recommended for use by the wider musician community.

Scale Workshop has these aims in mind:

Scale Workshop puts a polyphonic synth right inside your browser. You can audition and perform your scales by playing with a connected MIDI controller, QWERTY keyboard, or by using the touch-screen overlay.

Convert scl files and convert tun files to various tuning formats. Export formats include Scala .scl/.kbm, AnaMark TUN, Native Instruments Kontakt tuning script, Max/MSP coll text format and Pure Data text format.

Share your scales with other people by copy-and-pasting the URL in your address bar while working on your scale. The recipient will instantly see your scale information and can play it using their keyboard. This is invaluable for communicating your tuning ideas with others, or allowing your musical collaborators to export your tuning in whatever format they prefer. Try it out.

Display frequencies, cents and decimal values for your tuning across all 128 MIDI notes.

Note that this list is incomplete.

This has been a labour of love for almost 2 years – I hope that many people will find it useful! If you want to share any work you’ve created with Scale Workshop then I’d love to hear about it.

Now that Scale Workshop is in a stable state, I am going to focus my attention back on composing new music and hosting the Now&Xen microtonal podcast.

Open Scale Workshop in a new window

Of all the software synths in the world, very few of them support microtonal scales. If you are a musician using Linux and open source software then your options are even fewer. It’s for that reason that I want to celebrate the news that amsynth 1.8.0 adds support for microtonal tunings!

amsynth is a virtual analog synthesizer that runs as a standalone or VST, LV2 or DSSI plugin. Its sonic characteristic is similar to other popular digital VA instruments – fantastic for leads, basses and stabby chords. It’s light on the DSP and the controls are very easy to understand, so amsynth will rightfully earn a place in my toolkit once I move my music production machine over to Linux.

The easiest way to get amsynth if you’re on a Debian-based distro is to add the KXStudio repositories and then install via apt. Assuming you already have the KXStudio repos on your system, simply run the following command:

sudo apt install amsynth

If you’re unable to use the above, download the source for amsynth 1.8.0 and build it.

Once you have amsynth up and running, microtunings can be loaded by right clicking the interface and selecting a .scl file. In addition, you can load up a .kbm file for custom key mappings.

If you need some Scala tuning files (.scl) to play with, generate some with my Scale Workshop browser tool, or install Scala itself. Scala is extremely powerful, though you need to install it to your PC along with all its dependencies.

Developers, TAKE NOTE of what amsynth developer Nick Dowell has achieved here – .scl and .kbm formats are BOTH supported. .scl files specify the intervals in the scale, and .kbm specify the base tuning of the scale, whether it is A = 440 Hz or something else entirely.

Without supporting both of these formats, a synth could barely be said to support microtonal scales at all. I’m so pleased that amsynth gets this right.

Judging by this page on amsynth’s GitHub, it looks like amsynth may become cross-platform in the future. Should this ever happen, then Windows and Mac users would also have access to this nifty, free and microtonal instrument too. I look forward to this and will follow amsynth’s progress into the future.

[Update Jan 2023: This article is quite old now. If you’re looking for something more user-friendly than Scala, try Scale Workshop. If you want to learn more about Scala, read on!]

When you want to edit photos, there’s Photoshop. When you want to listen to music there’s iTunes (if you’re a pro at life, there’s foobar2000). When you want to create your own musical scales, opening up endless possibility in harmonic and melodic expression, there is Scala. Scala is a multi-purpose toolkit for everything related to tunings, scales and microtonality. You have a hardware synth that you want to retune? Scala will do it. Or a softsynth? Scala can export the tuning files required to make that happen. Want to generate all kinds of crazy scales that you can use to compose new music? Scala has near infinite options for you to play with. Want to experiment with world music and historical scales? There’s a database of thousands on the Scala website.

Equal temperaments are scales that divide an octave into some number of equally big pieces. The 12 note scale of Western music is an example, as each semitone is of equal size. So you already have experience with equal temperament scales and didn’t know it.In Scala, equal temperaments are trivially easy to create!A popular thing that beginning microtonalists like to do is to try quarter tones. The quarter tone scale divides the octave into 24 notes. Let’s make the scale in Scala. Load up Scala, type this line into the text field at the bottom, then hit enter:

equal 24

Explanation: When you type the command equal, followed by a number, Scala will produce an equal-tempered scale with that number of notes in an octave.But it looks like nothing happened after we hit enter. We still need to check that the scale was created correctly. So type:

show

This will show you the tuning data for the equal temperament scale you just created. As below:

0: 1/1 0.000000 unison, perfect prime 1: 50.000 cents 50.000000 2: 100.000 cents 100.000000 3: 150.000 cents 150.000000 4: 200.000 cents 200.000000 5: 250.000 cents 250.000000 6: 300.000 cents 300.000000 7: 350.000 cents 350.000000 8: 400.000 cents 400.000000 9: 450.000 cents 450.000000 10: 500.000 cents 500.000000 11: 550.000 cents 550.000000 12: 600.000 cents 600.000000 13: 650.000 cents 650.000000 14: 700.000 cents 700.000000 15: 750.000 cents 750.000000 16: 800.000 cents 800.000000 17: 850.000 cents 850.000000 18: 900.000 cents 900.000000 19: 950.000 cents 950.000000 20: 1000.000 cents 1000.000000 21: 1050.000 cents 1050.000000 22: 1100.000 cents 1100.000000 23: 1150.000 cents 1150.000000 24: 2/1 1200.000000 octave

Explanation: The equal command that we just used has produced 24 items for us (24 notes in our scale). The show command lets us see those 24. Each of these shows some number of “cents.” The cent is a measurement of how wide or narrow an interval is. Notice that each interval in our 24-equal scale goes up by 50 cents. 50 cents is exactly one quarter tone. 100 cents makes up a semitone, and 1200 the whole octave. Cents are a useful measurement to get your head around if you want to compare tunings with each other.That’s enough staring at numbers. Time to hear these quarter tones for the first time. On the Scala interface you’ll see a button which says play. Click that button!

In the first part, we divided an octave into some number of equal parts. Amazingly, we are not limited to dividing octaves. We can choose to divide other intervals instead, such as a perfect fifth or whatever you like. But what’s the point?Every note in a non-octave scale has a unique identity. Consider that we know a note A as a note oscillating at 440 Hz, or some octave above (880 Hz, 1760 Hz) or below (220 Hz, 110 Hz, 55 Hz). If our scale doesn’t include octaves, then a note A won’t have any other counterparts higher or lower in the scale. This means that, as we climb up or down into different registers, we keep hitting unique note identities which haven’t been heard elsewhere in the scale!This approach is extremely fruitful for new sounds, sonorities and progressions. However composition technique must change drastically. For starters, there are no more chord inversions, since you can’t raise any notes up or down an octave. Of course, this makes voicing difficult too. But you gain a very wide variety of intervals to play with, and it will challenge and grow you as a composer to exploit non-octave scales. Just try it and see.Here’s how we do it. We’re going to create a scale which divides a perfect twelfth (an octave plus a fifth) into 13 equally spaced parts.

equal 13 3/1

Explanation: The equal command tells Scala that we’ll be making a scale where all notes are the same size. The number 13 shows that we want 13 notes. And that weird fraction on the end? That’s the big interval that will be split into 13 equal parts. Think of it as a pseudo-octave.Why 3/1? For now just take my word for it. 3/1 is a perfect twelfth. So rather than repeating at the 8th (octave), we’re repeating at the twelfth.Notice, if we don’t include the number 3/1, then Scala will assume that this is an octave based scale. (An octave, by the way, can be expressed as 2/1).Let’s see the cents values for the scale we created:

show

And the result:

0: 1/1 0.000000 unison, perfect prime 1: 146.304 cents 146.304231 2: 292.608 cents 292.608462 3: 438.913 cents 438.912693 4: 585.217 cents 585.216923 5: 731.521 cents 731.521154 6: 877.825 cents 877.825385 7: 1024.130 cents 1024.129616 8: 1170.434 cents 1170.433847 9: 1316.738 cents 1316.738078 10: 1463.042 cents 1463.042308 11: 1609.347 cents 1609.346539 12: 1755.651 cents 1755.650770 13: 3/1 1901.955001 perfect 12th

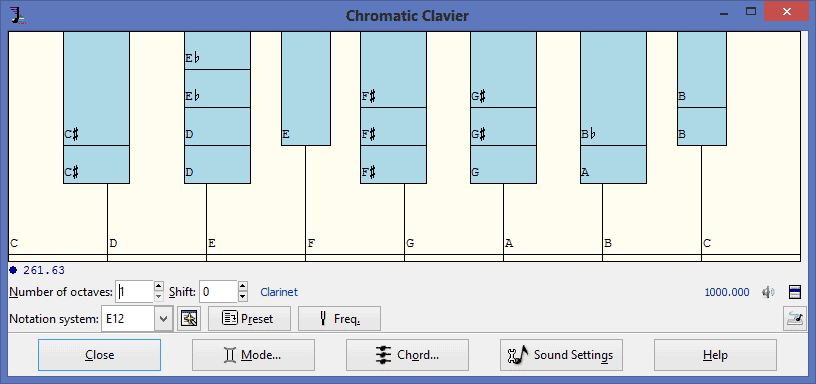

Can you remember how many cents are in an octave?The answer is 1200 cents. Looking at the above list of intervals, we can see there’s no value too close to 1200 cents at all. But there’s this nasty 1170 cents interval that’s gonna sound noticeably flatter than an octave. On the other hand, that perfect twelfth at 1901.955 cents, is purely in tune. Whatever this scale is, it doesn’t represent anything we’re used to in Western music. There’s no perfect fifth, no octave…The scale we’ve just created is none other than the Bohlen-Pierce scale, a famous non-octave scale with many interesting properties. It sounds very alien until you have taken time to immerse yourself in it. Jam with the chromatic clavier and hear it for yourself (remember, just click the play button on the Scala interface to do this).

The topic of just intonation (JI) is deserving of several books in its own right. It is an old mathemusical theory in which many cultures have their own take.What could a name like “just intonation” mean… If you think of “just” as meaning fair, right, exact, and perfect – and intonation of course having to do with the accuracy and flavour of the pitch – then you should get the general idea. Just intonation is a tuning system that uses exact, perfect intervals.In fact, the pitches of just intonation are made up of ratios. Think of numbers such as 2/1, 3/2, or 15/8. (These intervals are an octave, perfect fifth and major seventh, respectively).

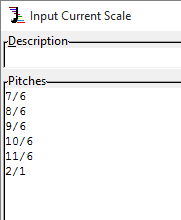

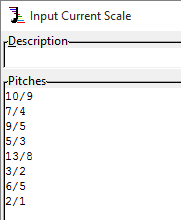

Time to get creative! There are many ways to go about making your own just scale, but here’s one way that can get you exploring quickly.On the main Scala window, click on the Input button to open up the Input Current Scale window. Here you can enter the pitches you want to use. In this case we’ll enter some fractions at random, following some simple guidelines.

Below are a few examples that follow the above guidelines.

You can also use Kyle Gann’s anatomy of an octave to find some interesting numbers to plug in.Once you’re done, hit OK and you’ll be taken back to the main Scala window. At this point you will find 9 times out of 10 that Scala says “Scale is not monotonic ascending.” If you saw this message then it means that the pitches of your scale are in a weird order. To fix this issue, tap the Edit button on the main Scala window, tap the Ascending button, and finally click OK.Let’s take a quick look at what you made:

show

Take a quick look at the interesting names that Scala gives to the ratios you randomly chose.Now it’s time to hear your scale! Hit the Play button to show the Chromatic Clavier. You can hold shift when you click to hold multiple notes down and hear that solid JI sound.Alternatively you can play your scale using a connected MIDI controller or MIDI keyboard. To do this just click the Relay button on Scala’s main window and then click the Start Relaying button.Repeat this process of JI scale creation a few times, each time playing your scale using a keyboard to get a feel for the unique musicality of each one.Once you become comfortable with this process and you get to know certain ratios that you love the sound of then you can start to ignore the guidelines I gave before.

Now you know how to come up with a just intonation scale of your own. But you still might not know why you would want to use just intonation. There are many differing opinions out there and it’s easy to find them using Google. And I recommend you spend a lazy afternoon doing just that. Here are a few suggestions: