Next Xen, a compilation album of music using alternative tunings, has just been released on the split-notes label!

The album features myself (Sevish), Banaphshu with Kraig Grady, Brendan Byrnes (ft. Louis Lopez), Carlos Devizia, Tony Dubshot, Jacky Ligon, Miekko, John Moriarty, Mosstone, Steve Mueske, Mythshifter, Robin Perry, Joseph Post, Carlo Serafini, Tall Kite, Elaine Walker, and Ozan Yarman (Ph.D.)

This free album is a snapshot of the online microtonal music community at the start of 2016 and shows a variety of approaches to groove-based microtonal/xenharmonic music. Check out the included liner notes to find out more about each artist and their approach to microtonality. If this is your first experience with microtonal music, then listen well and welcome to the madness!!

17 microtonal musicians come together to make an album of tasty xenharmonic beats. Make sure you download this one from split-notes.com when it arrives on February 6th.

I was reading some of Ivor Darreg’s writings and a really interesting idea jumped out.

“Try this: Move the bridge down until the 13th (instead of the 12th) fret sounds the octave of the open string. This will give an approximation of the 13-tone equal temperament.”

Here’s how it works. If you have a guitar with a movable bridge, then you can move it down such that the 13th fret gives you a perfect octave. This gives you a 13 tone scale to play on your guitar!

While its approximation to 13-edo is far from perfect (you’d need to completely move the frets for that) this should offer plenty of new tonal resources to the experimenting microtonal guitarist. Compared to 13-edo, the error is largest in the middle of the scale.

You can reverse this and push the bridge up such that the octave lies on the 11th fret, giving you a brand new 11-tone scale to experiment with. Again, it poorly approximates 11-edo but don’t worry about that, there are plenty of new sounds available through this method.

The idea can be pushed further:

“I fretted a guitar to 18-tone (Busoni’s proposed third-tones) and can use this guitar as a 17 or a 19 without the theoretical errors from moving the bridge spoiling any performances. So you can have three systems for the price of one.”

This really is “one weird trick that luthiers don’t want you to know!” Bwaha… ok I’ll see myself out the door.

For something a little different, check out 9 Alternative Tunings NOT for Guitar.

An example of a microtonal chord progression in 22edo (22 equal divisions of the octave, aka 22-tone equal temperament). These harmonies would be impossible to reproduce accurately using standard Western tuning, Arabic intonation, or basically any other traditional intonation. But with the new intonation systems that are popular within the xenharmonic scene, you might hear something new.

The tempo and velocity is controlled by a drunk walk using the drunk object in Max/MSP (Max 4 Live). Sound designs using Xen-Arts IVOR and FMTS2.

I’ve been following Dolores Catherino’s beautiful microtonal music for quite a while and it’s fascinating to get a look into her musical space. Everybody has a different approach to microtonality and hers is certainly different to mine. There are some very cool pieces of kit on display, like the Starr Labs Microzone U-648, H-Pi Tonal Plexus, Haken Continuum Fingerboard, and ROLI Seaboard.

This video also serves as a very inspiring introduction to why one would start using microtonal scales to push music into the future.

She also mentions that we could extend frequencies up above and beyond the range of human hearing (i.e. above 20kHz) with future advancements in sample rate fidelity and loudspeaker design. While it remains to be seen if this would have an effect on our perception of the music, it’s very interesting food for thought.

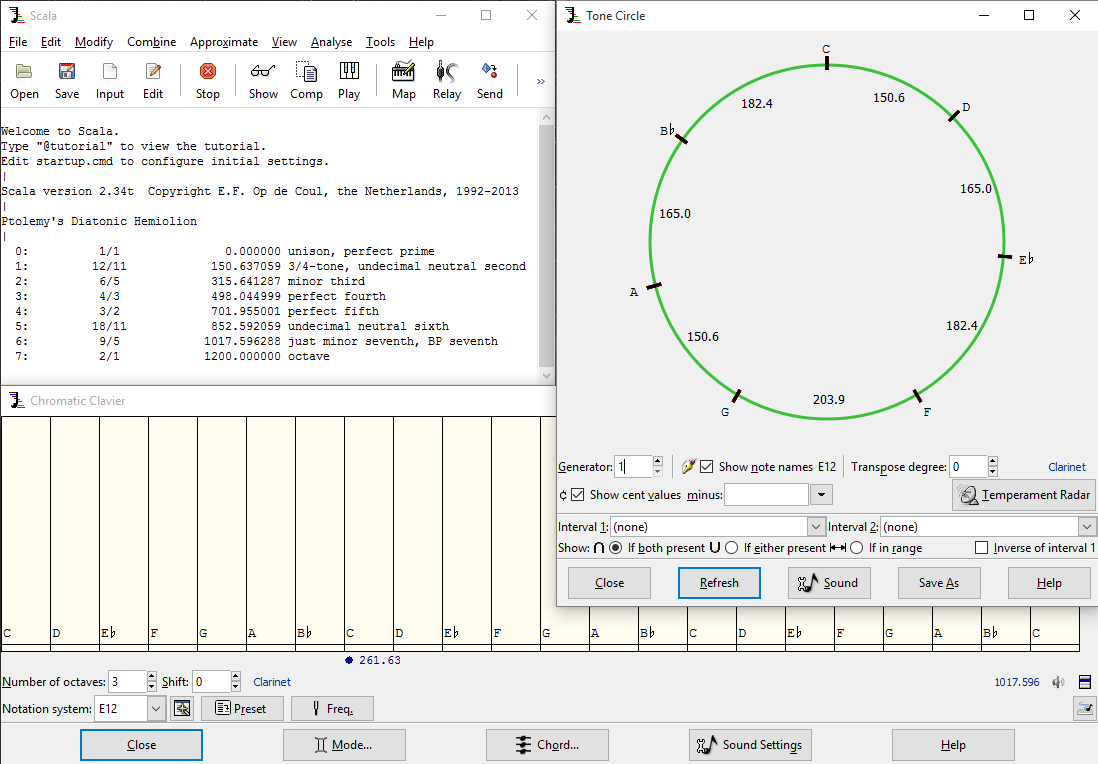

[Update Jan 2023: This article is quite old now. If you’re looking for something more user-friendly than Scala, try Scale Workshop. If you want to learn more about Scala, read on!]

When you want to edit photos, there’s Photoshop. When you want to listen to music there’s iTunes (if you’re a pro at life, there’s foobar2000). When you want to create your own musical scales, opening up endless possibility in harmonic and melodic expression, there is Scala. Scala is a multi-purpose toolkit for everything related to tunings, scales and microtonality. You have a hardware synth that you want to retune? Scala will do it. Or a softsynth? Scala can export the tuning files required to make that happen. Want to generate all kinds of crazy scales that you can use to compose new music? Scala has near infinite options for you to play with. Want to experiment with world music and historical scales? There’s a database of thousands on the Scala website.

Equal temperaments are scales that divide an octave into some number of equally big pieces. The 12 note scale of Western music is an example, as each semitone is of equal size. So you already have experience with equal temperament scales and didn’t know it.In Scala, equal temperaments are trivially easy to create!A popular thing that beginning microtonalists like to do is to try quarter tones. The quarter tone scale divides the octave into 24 notes. Let’s make the scale in Scala. Load up Scala, type this line into the text field at the bottom, then hit enter:

equal 24

Explanation: When you type the command equal, followed by a number, Scala will produce an equal-tempered scale with that number of notes in an octave.But it looks like nothing happened after we hit enter. We still need to check that the scale was created correctly. So type:

show

This will show you the tuning data for the equal temperament scale you just created. As below:

0: 1/1 0.000000 unison, perfect prime 1: 50.000 cents 50.000000 2: 100.000 cents 100.000000 3: 150.000 cents 150.000000 4: 200.000 cents 200.000000 5: 250.000 cents 250.000000 6: 300.000 cents 300.000000 7: 350.000 cents 350.000000 8: 400.000 cents 400.000000 9: 450.000 cents 450.000000 10: 500.000 cents 500.000000 11: 550.000 cents 550.000000 12: 600.000 cents 600.000000 13: 650.000 cents 650.000000 14: 700.000 cents 700.000000 15: 750.000 cents 750.000000 16: 800.000 cents 800.000000 17: 850.000 cents 850.000000 18: 900.000 cents 900.000000 19: 950.000 cents 950.000000 20: 1000.000 cents 1000.000000 21: 1050.000 cents 1050.000000 22: 1100.000 cents 1100.000000 23: 1150.000 cents 1150.000000 24: 2/1 1200.000000 octave

Explanation: The equal command that we just used has produced 24 items for us (24 notes in our scale). The show command lets us see those 24. Each of these shows some number of “cents.” The cent is a measurement of how wide or narrow an interval is. Notice that each interval in our 24-equal scale goes up by 50 cents. 50 cents is exactly one quarter tone. 100 cents makes up a semitone, and 1200 the whole octave. Cents are a useful measurement to get your head around if you want to compare tunings with each other.That’s enough staring at numbers. Time to hear these quarter tones for the first time. On the Scala interface you’ll see a button which says play. Click that button!

In the first part, we divided an octave into some number of equal parts. Amazingly, we are not limited to dividing octaves. We can choose to divide other intervals instead, such as a perfect fifth or whatever you like. But what’s the point?Every note in a non-octave scale has a unique identity. Consider that we know a note A as a note oscillating at 440 Hz, or some octave above (880 Hz, 1760 Hz) or below (220 Hz, 110 Hz, 55 Hz). If our scale doesn’t include octaves, then a note A won’t have any other counterparts higher or lower in the scale. This means that, as we climb up or down into different registers, we keep hitting unique note identities which haven’t been heard elsewhere in the scale!This approach is extremely fruitful for new sounds, sonorities and progressions. However composition technique must change drastically. For starters, there are no more chord inversions, since you can’t raise any notes up or down an octave. Of course, this makes voicing difficult too. But you gain a very wide variety of intervals to play with, and it will challenge and grow you as a composer to exploit non-octave scales. Just try it and see.Here’s how we do it. We’re going to create a scale which divides a perfect twelfth (an octave plus a fifth) into 13 equally spaced parts.

equal 13 3/1

Explanation: The equal command tells Scala that we’ll be making a scale where all notes are the same size. The number 13 shows that we want 13 notes. And that weird fraction on the end? That’s the big interval that will be split into 13 equal parts. Think of it as a pseudo-octave.Why 3/1? For now just take my word for it. 3/1 is a perfect twelfth. So rather than repeating at the 8th (octave), we’re repeating at the twelfth.Notice, if we don’t include the number 3/1, then Scala will assume that this is an octave based scale. (An octave, by the way, can be expressed as 2/1).Let’s see the cents values for the scale we created:

show

And the result:

0: 1/1 0.000000 unison, perfect prime 1: 146.304 cents 146.304231 2: 292.608 cents 292.608462 3: 438.913 cents 438.912693 4: 585.217 cents 585.216923 5: 731.521 cents 731.521154 6: 877.825 cents 877.825385 7: 1024.130 cents 1024.129616 8: 1170.434 cents 1170.433847 9: 1316.738 cents 1316.738078 10: 1463.042 cents 1463.042308 11: 1609.347 cents 1609.346539 12: 1755.651 cents 1755.650770 13: 3/1 1901.955001 perfect 12th

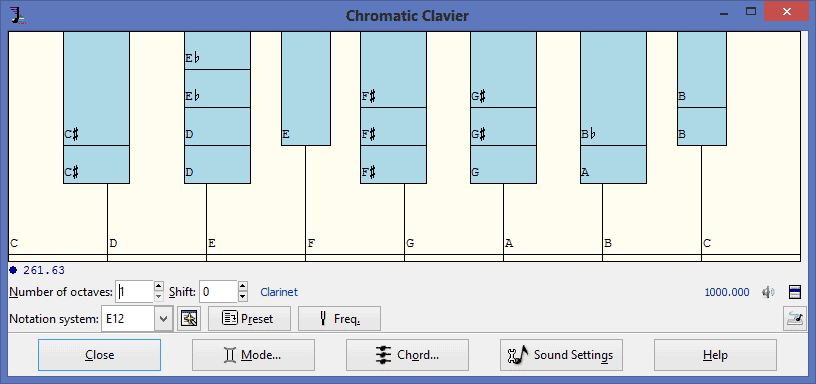

Can you remember how many cents are in an octave?The answer is 1200 cents. Looking at the above list of intervals, we can see there’s no value too close to 1200 cents at all. But there’s this nasty 1170 cents interval that’s gonna sound noticeably flatter than an octave. On the other hand, that perfect twelfth at 1901.955 cents, is purely in tune. Whatever this scale is, it doesn’t represent anything we’re used to in Western music. There’s no perfect fifth, no octave…The scale we’ve just created is none other than the Bohlen-Pierce scale, a famous non-octave scale with many interesting properties. It sounds very alien until you have taken time to immerse yourself in it. Jam with the chromatic clavier and hear it for yourself (remember, just click the play button on the Scala interface to do this).

The topic of just intonation (JI) is deserving of several books in its own right. It is an old mathemusical theory in which many cultures have their own take.What could a name like “just intonation” mean… If you think of “just” as meaning fair, right, exact, and perfect – and intonation of course having to do with the accuracy and flavour of the pitch – then you should get the general idea. Just intonation is a tuning system that uses exact, perfect intervals.In fact, the pitches of just intonation are made up of ratios. Think of numbers such as 2/1, 3/2, or 15/8. (These intervals are an octave, perfect fifth and major seventh, respectively).

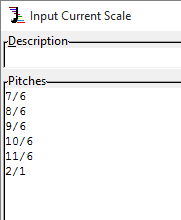

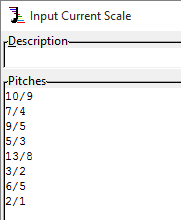

Time to get creative! There are many ways to go about making your own just scale, but here’s one way that can get you exploring quickly.On the main Scala window, click on the Input button to open up the Input Current Scale window. Here you can enter the pitches you want to use. In this case we’ll enter some fractions at random, following some simple guidelines.

Below are a few examples that follow the above guidelines.

You can also use Kyle Gann’s anatomy of an octave to find some interesting numbers to plug in.Once you’re done, hit OK and you’ll be taken back to the main Scala window. At this point you will find 9 times out of 10 that Scala says “Scale is not monotonic ascending.” If you saw this message then it means that the pitches of your scale are in a weird order. To fix this issue, tap the Edit button on the main Scala window, tap the Ascending button, and finally click OK.Let’s take a quick look at what you made:

show

Take a quick look at the interesting names that Scala gives to the ratios you randomly chose.Now it’s time to hear your scale! Hit the Play button to show the Chromatic Clavier. You can hold shift when you click to hold multiple notes down and hear that solid JI sound.Alternatively you can play your scale using a connected MIDI controller or MIDI keyboard. To do this just click the Relay button on Scala’s main window and then click the Start Relaying button.Repeat this process of JI scale creation a few times, each time playing your scale using a keyboard to get a feel for the unique musicality of each one.Once you become comfortable with this process and you get to know certain ratios that you love the sound of then you can start to ignore the guidelines I gave before.

Now you know how to come up with a just intonation scale of your own. But you still might not know why you would want to use just intonation. There are many differing opinions out there and it’s easy to find them using Google. And I recommend you spend a lazy afternoon doing just that. Here are a few suggestions:

Here’s an improvisation from a few years back, warts and all. It’s a microtonal piano piece.

Seems like there are tonnes of Max OS X users who want to get into microtonal music but don’t know how to jump in. Although I’m a Windows-using peasant, I wanted to gather up some ideas to start you off. Let’s dip in…

Logic Pro supports microtonal scales, and can even load Scala files! This can retune all of its built-in instruments and synthesisers (it doesn’t apply to any AUs or VSTs you’re running).

This online help file from Apple shows you how to find the tuning settings in Logic Pro X.

The big drawback—and I mean huge—it only supports 12-note scales, those scales must repeat at the octave, and each note can only deviate from 12-tet from plus or minus 100 cents (1 semitone).

These limitations restrict you to certain kinds of microtonal scales, and while there’s certainly room to explore within these limits, you’ll miss out on whole genres of microtonal scales that will blow your mind. You’ll miss the unimaginable cloud-like non-octave scales like Bohlen-Pierce and Wendy Carlos’ scales. Stretched-octave scales like Indonesian Slendro and Pelog also can’t be tuned faithfully. And large scales such as the 20-note eikosany, Harry Partch style just intonation, or large equal temperaments, are straight out unavailable.

Nevertheless, Logic makes it easy to microtune its high-quality instruments, even if it is crippled, so if you already own Logic then you should definitely check it out.

If you’re using a DAW that supports AU or VST plugins (such as Logic, Ableton Live, and some others) then you can make microtonal music by using certain plugins that support full microtuning. They can usually import a tuning file and that sets everything up for you.

It should come as no surprise that there are less *free* options for microtonal composition on a Mac than there are on Windows or Linux. But you can start with alphacanal Automat and Plogue Sforzando

If you’re willing to spend a little, then have a look through the big list of microtonal software plugins on the Xenharmonic Wiki.

Some people report success running Xen-Arts’ Windows-only VSTs using the free emulator WINE and a free VST host. If you’re of the technical mind to set up WINE, there’s a world of free VST synths for Windows awaiting you!

If you want to design your own tunings and export them for use in other instruments then there’s the Custom Scale Editor (CSE) software from Hπ Instruments. It allows you to tune every MIDI note to whatever pitch you want, exports tunings in a variety of popular formats and can retune the output of sequencers and notation programs. Thanks to Juhani Nuorvala for reminding me to mention it!

I heard that the now discontinued Lil’ Miss Scale Oven was the way to go. Really, I’ve heard wonderful things and wish I could have a little play with it myself.

It’s also possible to install Scala on OS X for free. I’ve never been through this process, but I’ve heard that it’s one of the most challenging things you can attempt to do.

Follow the instructions on the Scala website, and go slowly and carefully. You will be confused. You will have to install other things to get it to work. You will want to cry. But it IS possible…

Max/MSP, Pure Data and CSound are audio programming languages that can let you make sounds from the ground up. If you’re the tinkering type then try these!

Microtonal equal temperaments on a Max/MSP synth using expr

How to play microtonal scales on a Max/MSP synth

If you have any other methods of making microtonal music in OS X then get in touch so I can update this post!

I like to think that the machines were here on Earth since the beginning, and they were just waiting for the right time to show themselves to humans. They were making music in 12,000 BC and it sounded just like this new xenharmonic release over on the Dubbhism netlabel!

Strictly Binkie is all about self-generating modular dubbs (how many b’s are appropriate here)?!

You know how we roll… Free will is for losers, intelligent robots are taking over our planet. Hollywood and Silly Con Valley have been warning us for years, but Dubbhism is not sleeping on this. We bring you the next step in dubb: the Dubbularity. Big fat fully automated, self-generating, self-programming dubbs for the Kurzweil Generation.

Mixed by Binkieman, a dutch dub artist who’s custom built modular robosynth spits out weird algorithms, encrypted electronic messages, nasty basses and reverb-soaked rimshots. Bang the Binkie drum!!

Release page: http://www.dubbhism.com/2015/09/out-now-binkieman-strictly-binkie.html

Download: http://www.dubbhism.net/netlabel/dubbhism-netlabel-022-binkieman-strictly-binkie.rar